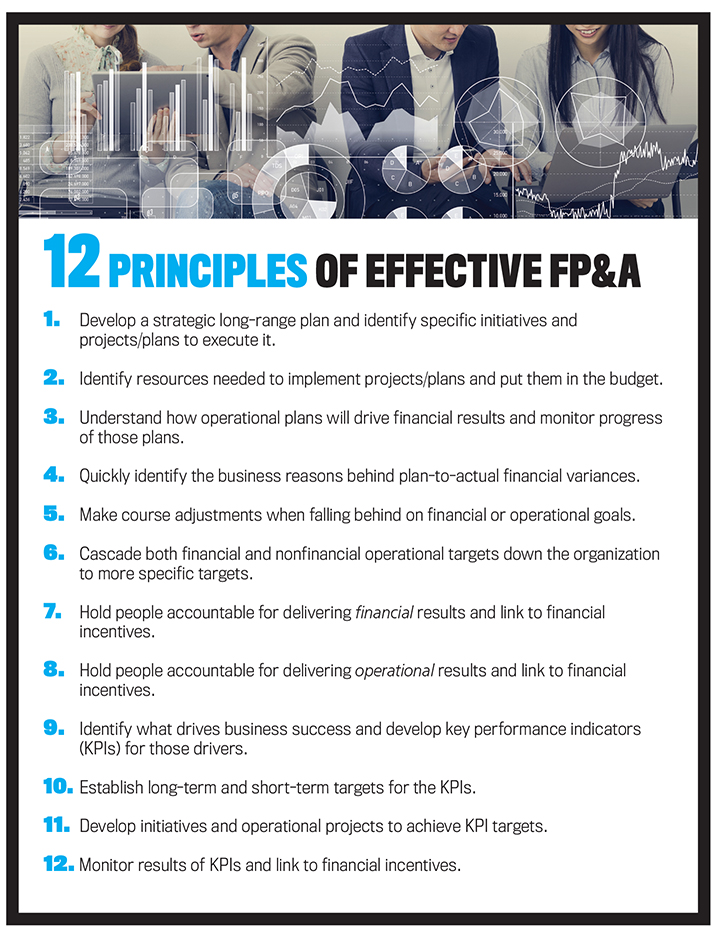

While aspects of FP&A may seem routine, such as budgeting or monthly variance reporting, they are all links in the chain of the value-creation process. Implementing and executing effective FP&A practices (see “12 Principles of Effective FP&A” below) requires a number of good practices. Let’s take a look at two areas: the people involved and selling management on the value of best-practice FP&A.

Statement on Management Accounting

This article is excerpted from the new IMA® Statement on Management Accounting (SMA), “Key Principles of Effective Financial Planning and Analysis,” published this month. It has been edited and abridged to fit in Strategic Finance.

SMAs present IMA’s position on best practices in management accounting. This newest SMA details 12 principles of effective FP&A and shows what the best-run organizations do differently with FP&A. It also discusses the role of technology, the competencies needed, how to get started, and how to “sell” the need for FP&A improvement to top management. The full SMA is available for download at bit.ly/2Y7frJP.

DEVELOPING THE SKILLS FOR FP&A

In many respects, the FP&A process is only as good as the people managing it. Executing the plan requires that people know what the plan is and their role in executing it. Key FP&A skills and capabilities include:

1. Understanding the Underlying Business

If FP&A staff are to become trusted advisors and partners in the business, they need to have a firm understanding of the underlying business. They need to know how the business is run, the major influences or levers of the business, who the customers are and how they buy, and the strengths and weaknesses of competitors. For example, one of the authors was hired as a new cost analyst at a factory making expensive food-processing equipment. One of his assignments was to track the costs of each project and estimate the final profitability. Although each project was specifically designed by engineers, there were always parts of the manufacturing process that could take more (or less) time than planned or parts of the product that were more (or less) expensive than planned. It was imperative that he understand the manufacturing process and employees to know what questions to ask.

Crucial to the business-partner role of FP&A employees is a solid knowledge of the business and its operations. This is how they can earn trust and build credibility. That trust and credibility are shattered when employees are perceived as having only superficial knowledge and, conversely, built up when they demonstrate in ways small and large that they are students of the business.

The best-performing organizations fuse together the operations and the financials of the business. That means it isn’t enough for FP&A employees to understand the financial side; they need to know the operational side as well if they’re ever going to be able to connect the two.

2. Building Effective Working Relationships Outside of Finance and Accounting

To successfully build working relationships, it’s essential to establish credibility. The people on the front lines know better than anyone else what’s going on in the business, and it’s the FP&A professionals’ job to learn and communicate that. They will be able to offer a real business explanation and insight if they have built good working relationships and are connected to and aware of what is going on around the company.

It isn’t enough to know that profit came in less than expected because cost of goods sold was higher than planned. That’s an accounting answer. Instead, discussions with the production manager might reveal the company faced a stock-out of a key material that had to be air-shipped at considerable cost to meet customer demand. Further business analysis may reveal that the demand forecast was off. To help safeguard that this doesn’t happen again, the analyst might meet with the sales manager to determine if this is another reason to implement the new sales and operational planning process proposed the previous month and currently under review. All of these findings are more probable through good working relationships with those outside of the finance department.

3. Understanding the Specific Area or Department They’re Supporting

Besides understanding the business, FP&A professionals also should understand the issues and language of the departments they support. For instance, the challenges of the logistics department are quite different than those of marketing or human resources. Each functional area needs FP&A professionals to understand its unique challenges and how it runs its side of the business.

Many of the more successful FP&A professionals will take practical steps to get to know the department they serve, such as attending weekly staff meetings or facilitating monthly reviews of plan vs. actual results. That way when the plan (or forecast) cycle starts up again, they are already part of the team.

4. Communication Skills

FP&A professionals need to be able to communicate effectively with the rest of the organization. Consider the monthly management reporting package that provides variance analyses to help executives understand what happened in the business and why. Ask yourself: How clear are the variance explanations? Could anyone in the organization read it and understand what is being communicated? Consider all the exhibits, reports, and templates used in the annual plan or monthly forecast. Do people outside of the finance department understand them and what they are used for? Are there actual business decisions being made based on these reports? If not, is that an indication of their lack of utility? To find out, ask the report recipients.

Better communication can also happen verbally when gathering facts. For example, to find an explanation for a financial variance, asking the right questions in the right way and avoiding ambiguity and forcing clarity can make all the difference in getting the best explanation. Likewise, using verbal skills to clarify an information request can avoid a lot of misunderstanding and rework. FP&A employees should take responsibility for communication and ensure all sides understand what is being asked and why.

FP&A staff members often make presentations during the planning process, as well as during monthly reviews, comparing actual results to the forecasts for the period. How those presenters express this information can either help executives grasp the issues quickly or leave them confused. One common complaint is that an FP&A staff member will display a chart crowded with data in small font and begin by saying “As you can clearly see…” The presenter hasn’t adequately provided context for what’s on the slide nor explained what’s on it. They’ve jumped right in, assuming the audience knows much more about what they’re looking at than they actually do.

5. Technical Skills

The number of technical skills that all management accounting professionals are expected to have keeps increasing. Excel, financial modeling, forecasting and budgeting, variance analysis, cost and profitability management, data analytics, return on investment (ROI) and net present value (NPV) development and analyses, accounting, and reporting are just the start. Other emerging technology skills include process automation, AI, business analytics, data security and storage, and data visualization.

Another emerging technical skill is project planning. This includes knowing how to develop a project charter (defining the goals, scope, approach, team structure, and so on) and a project plan (like a Gantt chart) with activities, tasks, resource estimates, milestones, and dates. As an employee from a best-performing FP&A company told us, “Effective FP&A can ensure coordination of initiatives, projects, and programs.” While FP&A professionals might not be leading the project, they may be tasked with managing it from a reporting and control perspective. Project management skills include being able to update the project plan as necessary, manage the progress reporting process, and facilitate meetings.

Beyond traditional financial modeling, the ability to develop a business case is another skill that is increasingly required. A business case includes how the investment would advance the strategy of the organization, the resource requirements, the estimated implementation timeline, alternatives considered and why the team chose a certain path, and how to package and present the plan.

All these various skills and competencies combine to help FP&A professionals become strategic business partners in their organizations. But before any FP&A improvements—and the related investments—are made, those professionals will often need to articulate and “sell” the value to the company’s executive team to get its buy-in. Doing so requires purposeful identification of what the expected benefits will look like and why they’re worth the cost.

SELLING THE VALUE TO MANAGEMENT

Convincing top management of the value of improving FP&A can be more difficult than expected. It’s difficult to measure the benefits of most administrative initiatives, such as improving the FP&A process. Most leaders consider the benefits of “intangibles” to be too difficult—if not impossible—to measure, so they don’t measure them, which leads to little to no improvement in the FP&A process. Like other more tangible operational improvements, they want to see the ROI first.

So how do we measure the expected value for investing in FP&A? If we define measurement as “a quantitatively expressed reduction of uncertainty based on one or more observations,” virtually anything can be measured. (Much of this section is based on two sources: Douglas W. Hubbard’s book How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of ‘Intangibles’ in Business and “Measuring the ROI on FP&A,” a presentation given by Gavin Black, Bill Sayer, and Amber Bowden at the Association for Financial Professionals (AFP) Annual Conference on October 27, 2013, in Las Vegas, Nev.) By defining specifically what an improvement in FP&A would look like, we can estimate the operational and even financial benefits. Here are four steps to do so.

Step 1: Decide to measure the benefits of better FP&A

There are several potential direct and indirect benefits of improved FP&A. Direct benefits, in which something should noticeably improve, include (1) identifying improvement projects, (2) determining if planned improvements were accomplished, (3) identifying process strengths and weaknesses, and (4) establishing priorities for future investment. Indirect benefits can include increasing communication between the FP&A team and the rest of the organization, better understanding of the potential value of the FP&A function, and more effective FP&A outputs.

To measure the benefits of better FP&A, identify likely benefits, who will benefit, and from whom you need buy-in. In other words, make a case for the improvement with supporting evidence. You will need to estimate the cost in people’s time and money, as well as what current practices could be reduced. Be aware from the start of expected challenges and how to address them. Common challenges include lack of support and resources, time constraints, measuring the value of “intangible” benefits, and defining the scope of the measurement. If all this sounds doable, proceed to the next step.

Step 2: Define the measures and collect data

Defining the measures means agreeing on what improved FP&A would look like and how it can be observed (for example, improved speed, cost, quality, satisfaction, motivation, influence, and engagement). A good place to start is talking with all the key players and asking them to identify ways that better FP&A could help optimize the decision-making process. Talk about current and past management decisions and how the various FP&A principles could make a difference.

In his book, How to Measure Anything, Hubbard recommends that before we decide how to measure something, we first must clarify the measurement problem by asking the following questions:

What is the decision this measurement is supposed to support?

Before deciding what to measure, the first step should be to identify the problem and decision for which you intend to use the measurement. For example, if you want to measure employee engagement, first decide why you want to measure it. Is the purpose to help improve quality of work or change hiring and development practices? Or if you want to measure the value of a proposed FP&A improvement initiative, is the purpose to decide whether to implement a new FP&A system or to improve the staff’s data analytics skills?

What specifically would the thing being measured look like as it relates to the decision being asked?

The key to measuring something that seems hard (or impossible) to measure is to ask what it would look like specifically. For example, if your decision purpose is to measure employee engagement to help decide whether to improve hiring and development practices, what would be observable signs of improved employee engagement? Potential answers could be less absenteeism, more ideas generated, fewer defects, or other specific observable actions relating to engagement and strategic or operational goals.

If the purpose is to measure the value of a proposed FP&A improvement initiative to improve the staff’s data analytics skills, potential measures might be the before-and-after impact levels of FP&A reports, process improvements identified, forecast accuracy, and new business opportunities identified.

Unfortunately, the contributions of the FP&A team often aren’t readily apparent. They’re more commonly noticed when there’s a mistake or lack of information rather than when they are helpful and accurate. But to measure the impact of a potential FP&A improvement initiative, we need to be specific about what we would be looking for. What does improved FP&A look like? Here are some examples of observable items.

Accurate and timely financial reporting:

- Impact of FP&A reports for the monthly executive business review meeting.

- Timely internal and corporate parent close.

- Effective compensation support.

Process improvement analysis:

- New ways to improve efficiencies and cost savings.

- Identifying waste, fraud, and abuse.

- Terminating expired or ineffective contracts and expenses.

- More or better metric reporting.

Business support and analysis:

- New business development opportunities identified.

- Improved forecast accuracy.

- Better cash management to achieve net positive interest cash flows.

Once there’s agreement on what better FP&A would look like and how to observe it, the next step is to identify how to collect the data. Potential sources of data include the various information systems, human resources, interviews, minutes of meetings, focus groups, surveys, and so forth. It may also take a different mind-set among the key players. Unfortunately, not every measure has readily available data such as units produced. But if you have defined what you are looking for, then observing that thing becomes a measure. For example, how often have we observed the FP&A team identifying new business development opportunities? To measure the impact of FP&A reports for the monthly executive business review meeting, the observation may be answering the question, “Are we using FP&A analysis more in our strategic decisions?” Or “Are more/deeper questions being directed toward the FP&A team?”

What is the value of additional information?

Information adds value to the extent that it reduces uncertainties in decision making. Knowing the value of the information helps us to identify not only what to measure but how to measure it. Sometimes just a few observations can reduce the level of uncertainty significantly, and collecting additional observations may have diminishing benefits. There is also the cost-benefit side of collecting additional measurement information. If the decision outcome relates to deciding whether to invest in an opportunity that could net $1 million per year, it would probably make sense to spend $10,000 to collect the additional information to help reduce the potential risk of making a poor decision. On the other hand, if the potential outcome is $10,000, then it would probably not make sense and a simpler way should be found to reduce the risk of a poor decision.

Step 3: Calculate the net value of improved FP&A

Calculating the value of intangibles like the potential value of an FP&A investment is easier said than done. An important contributor in this area was Enrico Fermi, a physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938 for his work on nuclear energy and who was also a master estimator with a knack for finding intuitive ways of measuring things that seemed too complex to measure. The Fermi method means to decompose the measurements into specific questions leading to a quantitative decision model. We break up the estimated costs/benefits into things we can observe, such as “Is it more than X?” The monetary values for each benefit or cost by year can themselves be decomposed further into more variables.

Applying the Fermi method to calculate the value of improved FP&A analysis, such as an efficiency improvement, could be done by multiplying the number of people working in the improved process, the cost of each person per year, the percentage of time spent on some unproductive activity, and the percentage of that unproductive time that was eliminated. Remember that the first year for most initiatives includes up-front investments that lower the net value for the first year. Thus, the analysis should extend beyond the first year depending on the time frame of the expected benefits. To get the needed buy-in from the key players on the estimated benefits and costs, the analysis should be logical and the estimated benefits should clearly exceed the expected costs.

Step 4: Refine and evaluate THE measurement process

Estimating the costs and benefits of FP&A improvement initiatives can improve over time through periodic reviews, satisfaction with the process, post-project audits, and continued working together with other departments and upper management to refine the estimation process. Estimating skills can be improved through calibration techniques, according to Hubbard. If estimates of benefits are shown to be reliable over time, top management is more likely to buy off on future improvement initiatives.

DELIVERING VALUE

FP&A has the potential to provide valuable decision support for the many decisions made during the planning process and as the strategic plan is executed. But it also requires FP&A staff to invest time to get to know the specific areas they support, develop relationships, and build trust and rapport to provide business analysis specific enough to make a difference. Building effective working relationships outside of the finance department—and understanding the underlying business and the departments they are supporting—will go a long way toward becoming business partners. Further, the burden is on FP&A staff to communicate effectively with the rest of the organization. They will need those skills to convince top management of the value that improved FP&A will provide in making strategic and tactical business decisions. To do so, they will need to articulate and be prepared to measure those benefits.

Q&A with Author Lawrence Serven

SF: What’s an effective way for an FP&A worker to become a trusted advisor and earn a seat at the table?

Lawrence Serven: An easy way to get started is to ask to be invited to the weekly staff meetings and offer to take notes. Helping your partner organization understand monthly financial results and how they compare to plan is a normal part of the job, but invest time to dig past the superficial explanations into the underlying causes. Most importantly, keep your eyes out for opportunities to contribute to special projects, prepare presentations, and provide decision support.

SF: What’s a common pitfall or mistake that FP&A employees should be wary of when executing their various roles?

LS: We’re numbers people, and for most of us our comfort zone is analyzing the data. That’s actually quite important and can deliver real insight. But don’t stay stuck there. Get out from behind your desk and get to know the people in the business area you’re serving—what they do, how they do it, what their goals are, etc.

SF: Once the FP&A team is in place and has begun to implement the 12 principles, what are some of the signs an organization should look for to know it’s on the right path to best-practice FP&A?

LS: One clear sign is that the finance team is being invited to meetings outside of the “must-attend” budget sessions. Finance is being included on project teams, in staff meetings, and at events inside and outside of work hours. The questions they’re asked are much more strategic in nature. They’re sought-after business partners, and key decisions are being made with finance (rather than finance being told after the fact).

SF: How often should FP&A employees meet with the departments they serve to keep lines of communication open?

LS: While the early days of relationship building may be heavily scripted with formal meetings, interactions will be much more fluid and informal as the relationship continues. The cadence of your meetings will naturally evolve over time and may differ by business partner—some will want to interact with you more than others. You’ll know you’ve gotten somewhere when your business partner starts to casually drop by your workspace to talk.

SF: Are there practical steps FP&A practitioners should take to get started?

LS: Think of ways to learn the “everyday business” of the area you support. For example, an FP&A manager at a major U.S. utility company told me about how she got to know the business. She would go out with work crews one day a week every month. It meant showing up at the office at 6 a.m. and a long workday. Over time, it won her the trust and respect of the entire organization. She’s now the trusted business partner she sought to be.

July 2019