While the CEO’s strategy in this hypothetical acquisition scenario is smart, and in many ways indispensable to striking a good deal, incremental value projections can suffer from management’s overenthusiastic forecasts with regard to the actual benefit of a merger or acquisition. But from my experience as a CFO who has initiated, negotiated, and completed many successful acquisitions, it doesn’t have to be this way. At the outset of the valuation process, putting together an expansive, inclusive acquisition team with operational experience—then actively involving the team in every aspect of the valuation process—can greatly improve the odds of creating an acquisition valuation that minimizes, or even is devoid of, these forecast overestimations.

ELEMENTS OF INCREMENTAL VALUE

The acquisition team can and should organize the incremental values into the following four categories:

- Products and Services—expanding and improving what the buyer and the seller market and distribute.

- Customers and Markets—expanding to whom they each sell.

- Economies of Scale—reducing costs as a percentage of revenues by merging operating and overhead functions.

- Intangibles—valuing the improvements (or even detriments) in revenues, and reduction (or additions) in costs, which can be envisioned but not directly estimated in dollar terms.

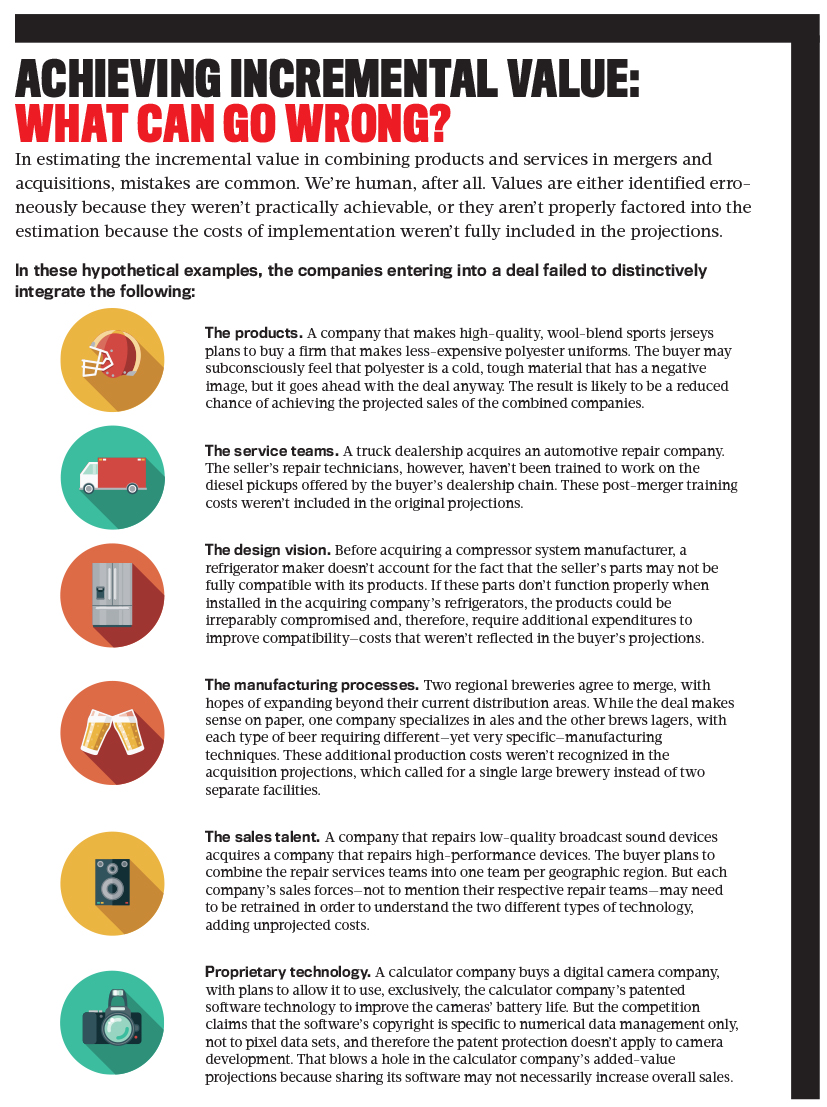

Problems begin to arise when the acquisition team becomes overexuberant about what’s theoretically possible for the deal or fails to project the additional investment necessary to attain the achievable. This overexuberance can be expressed in many ways. For one, avid acquirers have been known to envision future value that can’t be achieved physically. Deep team review procedures, however, can help uncover and avoid most of these situations. This same attention to detail during the initial valuation stage of the bidding process can promote an evaluation process that penetrates the depth of important assumption details to identify conditions or situations that create unconquerable barriers to value creation.

For buyers, a further challenge is to avoid over-relying on the seller to provide key information that could weigh on the transaction. Understandably, the seller will tend to promote only the positive. In my experience, however, these sorts of preventable valuation errors can often be avoided by having detail-level operating personnel—including managers in marketing, manufacturing, sales, and distribution—on the valuation team.

The top executives charged with prospectively either adding to the business or merging it into another are understandably enthusiastic to be expansive, creative, historically perceptive, and visionary. Yet, at the same time, they can also be equally (and understandably) capable of ignoring or failing to fully consider important tempering aspects of the valuation process.

COMBINING PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

So what are some realistic synergies that people in the C-suite should expect from a successful merger or acquisition? Two of the most obvious are vertical integration, which merges a key component of the chains of operation of the buyer and seller, and horizontal integration, which brings together families of products or service offerings that provide customers with more fully integrated solutions.

But there also are plenty of opportunities to share development skills, marketing talent, technical capabilities, proprietary products or services, competitive knowledge, and business projections. This propensity to “share” or “combine” in order to achieve further incremental value between the two companies extends to customers and markets as well. Key among these opportunities are:

- Combining geographic dominance to merge established sales, marketing, and distribution efficiencies.

- Merging specific customer lists in marketing to take advantage of established customer relationships and create service efficiencies.

- Adopting a common marketing media to entice customers of one of the companies to spontaneously purchase the products and services of the other company.

- Merging brands to extend the value of dominant branding.

- Acting on customer feedback to apply existing marketing improvement techniques and programs to the new company.

- Planning for market evolution to adopt a product enhancement plan that may have been created by the other party to the deal.

Mergers can lead to unexpected, and therefore unprojected, losses in value with respect to customers and markets. Say, for example, a cherry wood furniture manufacturer acquires a marble furniture maker, in time causing the buyer to lose its special identity as the “hardwood king.” The seller, in turn, loses its local niche as the premier quality living room furniture provider, contributing to unprojected sales declines for the combined company.

PITFALLS OF EXPANDING THE CUSTOMER BASE AND MARKETS

Many companies looking to merge or take part in an acquisition frequently overlook the role their customers will play in any deal that’s brokered. For example, retail chain customers may routinely purchase from both companies. When those suppliers merge, however, customers may seek additional (and unforeseen) volume discounts. Even something as simple as combining product catalogs could hurt sales if customers can’t easily find what they’re looking for in the “new and improved” catalog. What initially sounded like a cost savings may turn out to be anything but.

Other mergers and acquisitions fail to account for the specialized sales expertise of both parties to the deal. For example, a company that sells bicycles may purchase one that sells motorbikes, both dealing through multiple distribution channels, including chains that sell outdoor gear. Problem is, those who know the ins and outs of bicycles may know little or nothing about motorcycles. These salespeople can be trained, of course, but these costs may not have been accounted for before the merger.

In the previous example, each company’s designated salesperson has developed a close, special relationship with the chain manager in charge of purchasing each line of bikes. If those personal relationships are disrupted in any way, it could result in unprojected sales losses or additional costs to the new company.

Finally, it’s easy to extend expected market evolution in one sector to future results in another. What do I mean by that? For example, doing business in an emerging country undergoing rapid, expected, free-market development may be very different from doing business in a country with a mature market. Distinctions in the markets may dictate different future expectations, something that a sharp acquisitions team needs to take into consideration during its planning phase.

ECONOMIES OF SCALE

Significant cost reductions, both administrative and operational, may be the most universally forecasted incremental value production in prospective mergers and acquisitions. These include potential cost-saving opportunities like obtaining bigger volume discounts on office and production materials, eliminating overlapping administrative positions, and achieving operational efficiencies, such as in warehousing and distribution.

Not surprisingly, though, people are going to make mistakes when facing a nearly endless list of problems in effecting economies of scale in a merger. These errors are largely borne out of enthusiasm for the positives that jump out of the deal and the natural tendency to envision the future more theoretically than realistically. For buyers, specifically members of top management, the key is to recognize the possibility of these errors and problems and predict what’s likely to occur—not what’s theoretically most valuable.

Over the years, I’ve witnessed or heard of plenty of examples of operational failures to achieve projected incremental value in economies of scale. In no particular order, here are six examples of common stumbling blocks I’ve encountered or identified:

- Jeopardizing established relationships. The buyer’s director of purchasing has developed a strong working relationship with his company’s specialty steel product design team. Likewise, the seller’s director of purchasing understands the special needs of her company’s alloy products designers. One of these relationships would likely falter if the combined companies decide to eliminate one director of purchasing, with the result that the projected cost savings may be unattainable.

- Aiming too high. The buyer’s distribution director has a post-merger improvement list that includes ways to save money. Two of the ideas are to implement a highly efficient product-number tracking system for both companies and to merge a few of the warehouses. Because these are both ambitious goals involving lots of time and energy, it’s possible that one (or both) won’t get implemented or will be less than fully implemented. Therefore, the projected savings won’t be realized.

- Overlooking initial consolidation costs. The buyer adds a value element for standardizing the manufacture of a key subcomponent with the seller but doesn’t recognize the up-front cost of retooling one of the factories and retraining its workers. For example, a company that publishes hardback books is evaluating the acquisition opportunity for a firm that publishes journals. In estimating the acquisition value, the book publisher determines that it can print the journals during its third shift. So it builds into the value of the deal a reduction in nonvariable operating costs, such as facilities insurance, by closing the journal production plant. But it fails to add the cost of moving and reinstalling the journal production machinery to its acquisition costs. These are the kinds of expenditures that can be overlooked in the projection process.

- Making uninformed projections. The CFO of a long-haul trucking company proposed, and the acquisitions team projected, value for trimming the number of truck drivers. One problem: The CFO and her team didn’t know that the VP of manufacturing had negotiated and contractually agreed with the union that every driver’s position is safe.

- Ignoring possible emotional difficulties. The buyer’s CFO wants to merge the companies’ accounting departments into one, but the seller’s CEO, whose continuance is important, admits he’ll have a very hard time eliminating his personnel. This, too, projects unachievable cost savings.

- Looking at only the positive. I call this “contagious deal enthusiasm.” It’s both common and understandable for the acquisition team to focus on the happy, often intangible, consequences of the merger while downplaying or even ignoring the challenges. For example, a buyer that sells fresh specialty vegetables in New England acquires a seller that butchers and distributes specialty meats in California. They’re so enthusiastic about the opportunity of eventually improving the numbers of both companies that they ignore the fact that there’s little opportunity for sharing creative success factors between the different product lines.

WHAT ABOUT INTANGIBLES?

No matter how meticulously any merger or acquisition is planned for, certain things will invariably be ignored in the valuation process. Failure to recognize these intangible effects can cause a potential buyer to be outbid by a more confident, visionary competitor, thereby losing an attractive deal. But in many cases, intangibles—whether accounted for ahead of time or not—can bring value to the new organization. Here are several that may be tied to the deal, for which no reasonable dollar measure is available:

- Stock market enthusiasm. The market tends to embrace size and market penetration.

- Management enthusiasm. Management can become reinvigorated by major, potentially positive challenges.

- Management talent cross-training. Management enjoys teaching to and learning from each other, both formally and informally.

- Advanced software utilization. Combined adoption of the more advanced software—more often the buyer’s software—will bring intangible value to the other company’s operations.

- Improved talent recruitment. It’s generally easier to attract national talent to a larger enterprise.

- Employee turnover reduction. In the larger, integrated organization, there’s more opportunity to find the position that best suits the individual.

- Lower external recruitment. Larger organizations have larger talent pools from which to promote employees into open positions.

- Employee cross-motivation. With an acquisition, employees of both companies have a new incentive to show their counterparts what creative things they can do.

- Positive public perception. A merger can provide an unmeasurable but undeniable benefit: the general perception that a larger company provides a fuller range of products and services to a deeper array of customers over a broader scope of market.

SEALING THE DEAL

As you can see, there are a number of challenges to projecting the value of any deal involving a merger or acquisition. A lot of what needs to be considered is right there on the surface—the financials, hard assets, and a diverse, talented workforce—but there’s plenty that may escape the eyes and ears of even the sharpest acquisition team. And when emotions come into play, even the best-laid plans can hit a serious pothole on the road to a mutually beneficial deal.

Thankfully, I’ve found that most teams do a vigorous, creative, and visionary job of finding all the achievable and expected net incremental values in putting companies together. They vividly meet the challenges and are clearheaded in reflecting that the incremental value in any deal is that value which can be realistically achieved, not theoretically dreamed.

When it comes time for your organization to consider a deal, make sure your acquisition team consists of operational leaders at the highest levels in order to ensure that your competitive, value-maximized bid will represent achievable values and not those that are unrealistic. If it’s successful, you’ll have the thanks of your new employees, shareholders, and customers—not just in the weeks and months after the deal closes, but for many years to come.

March 2019