As the consulting work performed by Certified Public Accountant (CPA) firms increases and mergers and acquisitions (M&As) become more complex, regulators are signaling their concern over auditor independence. Cautionary reminders have been announced, action has been taken against firms and individuals, and regulatory authorities worldwide have updated the rules for auditor independence. The U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) is increasing enforcement, issuing disciplinary actions, and calling on all parties, including auditors, audit committees, and executive leadership, to remain vigilant in monitoring independence. As a result, the C-suite has a critical role to play in identifying and addressing situations that could impair independence, such as M&As. The SEC has put audit firms on alert due to the significant growth in consulting work, which has more than doubled since 2010, during a time when corporate M&As are also on the rise. According to Dealogic data, worldwide M&A value increased more than 25% between 2016 and 2021. The SEC is concerned that the result will be auditors performing prohibited work for audit clients and is therefore implementing new initiatives to investigate independence violations.

Renewed Scrutiny on Auditor Independence

Public comments by top regulators indicate that the SEC is intensifying its focus on enforcing independence violations. According to Dave Michaels in Big Four Accounting Firms Come Under Regulator's Scrutiny, the SEC’s enforcement director, Gurbir Grewal, warned in December 2021 that the SEC “will have a firm commitment moving forward to continue to target deficient auditing by auditors, auditor independence cases, [and] cases around earnings management.” Michaels also reported that the SEC’s Miami office sent requests for information about auditor independence to the Big Four and smaller public accounting firms. Firms were asked about liability contracts and contingency fees dependent upon specific outcomes.

How serious is the SEC about the violation of independence rules? In October 2021, the SEC’s acting chief accountant, Paul Munter, issued a press release to “all gatekeepers in the financial reporting ecosystem (auditors, management, and their audit committees)” for vigilance regarding auditor independence. He cautioned that the responsibility for independence belongs to the audit committee and the client, as well as the auditor. Munter cited an example of non-audit services and business combinations, noting that management, the audit committee, and the auditor should proactively monitor situations that could impair auditor independence prior to business combinations.

Munter clarified that, given that all listed firms are required to hire an independent auditor, they share this responsibility. Therefore, as the client, the C-suite has a distinct role in monitoring independence issues that could arise from consulting engagements and M&A activities. As part of the executive-level responsibilities in setting and implementing strategy related to organizational goals, the C-suite has direct insight into factors that could impair auditor independence. Munter issued a similar public statement in June 2022 to reemphasize that accountants, audit firms, registrants, and their audit committees should continually “assess and approach auditor independence for purposes of considering, beginning, or continuing an audit engagement under Rule 2-01(b).”

A crucial aspect of the increased SEC scrutiny is the taking of names. Not only are the CPA firms named and disciplined in SEC enforcement actions, but individual audit professionals are also identified and sanctioned. In the SEC enforcement action against KPMG for the College of New Rochelle case in February 2021, where KPMG failed to identify serious fraud, the audit manager was personally named and received a one-year suspension and disciplinary action. In a 2021 case, not only were the audit firm and audit partners charged with violating auditor independence rules, but the issuer’s then-chief accounting officer (CAO) was also charged for his role in the misconduct. The SEC expects client executives to share the responsibility for independence; thus, C-suite executives should exercise vigilance because they can be held responsible for independence violations.

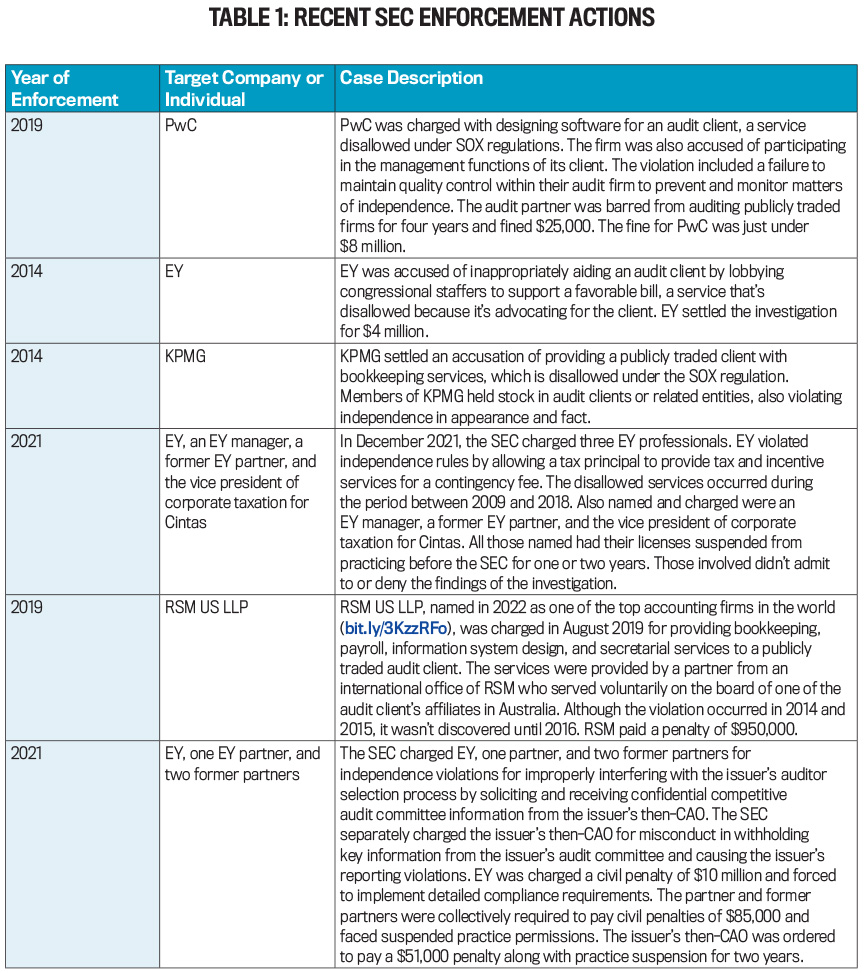

Recent enforcement actions reflect the SEC’s renewed focus on breaches of auditor independence. Although few SEC enforcement actions have named firm executives as the cause of violations to date, at least one recent case named the CAO and set a tone for the current regulatory climate. See Table 1 for examples of major auditor independence violations charged by the SEC in recent years.

A Summary of Independence Rules

According to the principles in the Code of Federal Regulations, Section 201.2-01, independence is impaired when “a relationship or…service:

• Creates a mutual or conflicting interest between the accountant and the audit client;

• Places the accountant in the position of auditing their own work;

• Results in the accountant acting as management or an employee of the audit client; or

• Places the accountant in a position of being an advocate for the audit client.”

Auditors are primarily governed by three regulatory bodies based on the type of clients they audit:

• Auditors of publicly traded firms in the United States must register with the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) and aren’t permitted to provide their publicly traded audit clients with any of the services listed below because they’re deemed to impair independence.

• Bookkeeping

• Financial information systems design and implementation

• Appraisal or valuation services, fairness opinions, or contribution-in-kind reports

• Actuarial services

• Internal audit outsourcing services

• Management functions or human resources

• Broker-dealer, investment adviser, or investment banking services

• Legal assistance and expert services unrelated to the audit

• Auditors of privately held firms in the U.S. adhere to rules set forth by the Auditing Standards Board (ASB), a 19-member committee designated by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA).

• Auditors of international firms fall under the regulation of the national auditing standards of the 130 member countries and jurisdictions of the International Federation of Accountants. The professional accountancy bodies representing each area are encouraged to eliminate material inconsistencies compared to the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

In addition, countries can impose their own restrictions; for example, Europe allows consulting for audit clients but restricts the total revenue earned.

Updates Regarding Auditor Independence

Auditors of all firms face new auditor independence rules for publicly traded, privately held, and international clients. In order to play an active role in monitoring and maintaining independence, the C-suite should remain up to date on auditor independence rules.

The SEC changed its rules on auditor independence in an update published on October 16, 2020. The SEC press release revealed that auditors will no longer be considered to have impaired independence due to standard consumer and student loans. For example, when an audit partner who isn’t on the audit engagement has a student loan with an audit client that’s a large student loan company, this no longer results in an independence violation.

Another amendment addresses problems with non-audit services to entities prior to a merger or acquisition of a client firm, or non-audit services provided to client affiliates that aren’t considered influential. The new rules effectively relax the standards for independence in these situations. Over the past decade, SEC staff conducted a number of consultations where otherwise unaffiliated audit clients created an independence violation for an auditor because the firms were all portfolio companies of an investment fund. When one firm goes public, the allowed services to other portfolio firms become an independence violation for the auditor of the client registering with the SEC. Other than the investment fund relationship, the other firms “have no impact on the entity under audit in any way and do not affect the objectivity and impartiality of the auditor in conducting the audit for Company X,” yet independence was violated because of the portfolio fund investment.

The amended independence rules resolve these issues that previously triggered auditor independence violations but represented no significant threat to the auditor’s objectivity. The amended rules also provide a transition provision for independence violations resulting from M&As. But the SEC expects the independence violation to be promptly corrected and preferably before the effective date of the merger or acquisition.

The new SEC rules prompted the Professional Ethics Executive Committee (PEEC) of the AICPA to reevaluate the rules for auditors of privately held clients. Among the concerns addressed are certain consumer and student loans owned by auditors, and the proposed change would allow more flexibility for auditors, similar to the change by the SEC. But the PEEC is also considering the addition of loans held by immediate family members in determining independence. Another proposed change is to add guidance regarding whether services provided to a client affiliate impair independence due to a merger or acquisition. The new rules were adopted in March 2022 and went into effect at the end of the year. Early adoption is allowed.

The International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA) is strengthening independence requirements by changing the term “listed entity” to “public interest entity” (PIE) to refer to publicly traded firms and improving the definition of what firms qualify as PIEs. Transparency requirements are also being improved, requiring auditors to disclose the independence requirements of PIEs publicly. The new rules aren’t effective until December 15, 2024, but auditors are being encouraged to adopt the provisions before then. Corporations operating globally can benefit from gaining an understanding of what qualifies as a PIE and independence disclosure requirements to ensure they can adopt the new provisions before the deadline.

The Reasons for Scrutiny

Independence rules for publicly traded firms are subject to Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) rules that don’t allow firms to provide consulting services to audit clients. When SOX initially took effect in 2002, CPA firms reduced consulting services dramatically.

When the sweeping SOX regulations went into effect in June 2002, CPA firms were cautious in providing consulting services, but over time the proportion of consulting revenue at the largest auditing firms has climbed dramatically. Amanda Iacone reported on Bloomberg Tax that while audit revenue only increased by 19% since 2010, global consulting revenue grew by 136%. Tax and legal services revenue increased by 59% globally. In the U.S., three of the Big Four CPA firms initially spun off their consulting work after the SOX legislation but over time either acquired consulting firms or marketed consulting services to non-audit clients. Consulting revenue increased for Big Four firms in the U.S. from just under $5 billion in 2007 to almost $25 billion in 2018.

Iacone further noted that accountants may encounter unforeseeable independence violations due to the increasing complexity of the markets. M&As create a challenge in distinguishing between audit and non-audit client affiliates. If a consulting client is acquired by an audit client, auditors may face independence violations. This potential issue is also discussed in Paul Munter’s statement in June 2022. Munter noted that “[a]nother notable and increasing area of concern involves the provision of non-audit services. While non-audit services are often not provided directly to the company being audited, OCA [Office of the Chief Accountant] staff encounter circumstances in which the extent and magnitude of the non-audit services and business relationships between the accountant and affiliates and non-affiliates of the company being audited would make it difficult for a reasonable investor to conclude that the accountant could exercise objective and impartial judgment in its audit.” Overall, the increasing complexity of business restructurings and the provision of non-audit services could lead to independence violations if the auditor and the client firm fail to consider the implications for auditor independence.

Although few, if any, documented cases to date of independence violations are a result of M&A activity, this is likely due to the SEC’s transition provisions. But the SEC expects these independence violations to be corrected before the effective date of the business combination. Meanwhile, although the SEC’s revised independence regulation may improve the situation, another conflict arises if an auditor has provided advisory services for a potential buyer of an audit client or a potential target firm. Collectively, these new dynamics in auditor independence point to the central role of the C-suite in working with its auditor to maintain auditor independence and address potential threats to independence promptly.

Independence in the U.K., India, and Australia

Recent developments on the international stage indicate increased restrictions on auditor independence. In the U.K., following several high-profile accounting failures, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) recently issued a reform package requiring the Big Four to split their audit and consulting businesses within the next four years. The new requirements are intended to address audit quality issues due to the significant growth in consulting revenue. The FRC reports that audit fees make up only about one-fifth of the Big Four’s combined total revenue of $13.7 billion.

In India, several firms like Deloitte, PwC, and Grant Thorton have halted the performance of non-audit services for their audit clients. Although these actions will result in significant loss of revenues for these firms, the voluntary action is seen as being in “the spirit of self-regulation and extends beyond non-audit services permissible under prevailing rules and regulations in India” (Deloitte to Stop Offering Non-audit Services to Their Audit Clients). Deloitte stated it expects the change to increase the public’s confidence in auditor independence.

In Australia, Edmund Tadros of the Australian Financial Review reported that EY plans to spin off its audit services practice to facilitate independence. The same can’t be said for the other Big Four firms at this time. According to Tadros, KPMG and PwC don’t plan to separate their audit services for now, and Deloitte has no comment. But John Dumay, a professor at Macquarie University, predicts that, since the Big Four firms were already ordered to split their audit and non-audit practices by 2024, Australian regulators will be pressured to do the same.

These examples highlight another vital element of the C-suite’s role in auditor independence issues. An auditor who has developed valuable expertise on the company’s audit engagement over several years may have to cancel the audit relationship. The C-suite should consider whether or not such an outcome leads to increased audit risk as a result of the lost expertise on the audit engagement.

Takeaways

Overall, the SEC is signaling increased efforts in enforcing auditor independence violations. The stakes related to independence are high because, combined with any other missteps in due diligence, a violation of independence draws intent into question should errors occur. The SEC calls explicitly on the audit committee and firm executives to play a part in ensuring auditor independence, and the C-suite has the distinct, high-level view to be able to monitor and identify situations that could potentially impair auditor independence, especially those involving business combinations.

CPA firms and firm executives who violate independence rules can face SEC fines, sanctions, and impaired reputation. Fortunately, there are practical and actionable items that can help firm executives navigate the changing landscape of auditor independence (see Table 2).

September 2023