Teaching business and sustainability—once a fringe topic at most business schools—has become an expectation at many institutions. Nearly 70% of prospective graduate students say sustainability is important or very important to their academic experience, according to a 2024 Graduate Management Admission Council survey. That interest mirrors what these students will experience postgrad. A 2023 Deloitte CxO survey found that climate change was the second most pressing issue for C-suite members to focus on over the next year—a notable priority as rising interest rates, global conflicts, and ongoing supply-chain issues currently command attention. On top of that, 75% of firms had either slightly or significantly increased sustainability investments from 2022 to 2023, according to the survey.

Amid this growing need for business students and leaders to be properly trained in sustainability, the question looms: How best can we teach sustainability topics to those who also face pressures to maximize profits? Can these perspectives go hand in hand? Or does teaching sustainability involve tradeoffs between doing what’s right for the planet and people and maximizing the firm’s profit potential?

We believe there’s a path for teaching sustainability in a way that aligns with pursuing profitability. We’ve taught business sustainability to hundreds of students at myriad levels of education and have developed customized executive education programs for corporations.

Through our experience, we’ve found that successfully teaching business and sustainability comes down to these four elements:

- Resetting perspectives with a reality check.

- Acknowledging the challenges of integrating sustainability and business.

- Stressing cogent, empirically testable arguments for sustainability increasing profitability.

- Avoiding the traps of becoming cheerleaders and know-it-alls.

Note that we’re focusing on how to approach these students, not what to teach them. Of course, content must be customized to the overall topic—teaching sustainability in an accounting class is different than in a finance or management course. But these four elements are universal.

Reset Perspectives with a Reality Check

Students might have a basic grasp of sustainability issues, but their views can be skewed by biases and half-truths. For example, ask students how much plastic gets recycled, and many will respond with a rate that’s much higher than reality (it’s between 5% and 9% in North America). On the other hand, some students will be too cynical, and might insist that companies’ sustainability efforts are just for show. This results in a classroom mix of optimists and skeptics who might hopelessly wonder: How can we make it better?

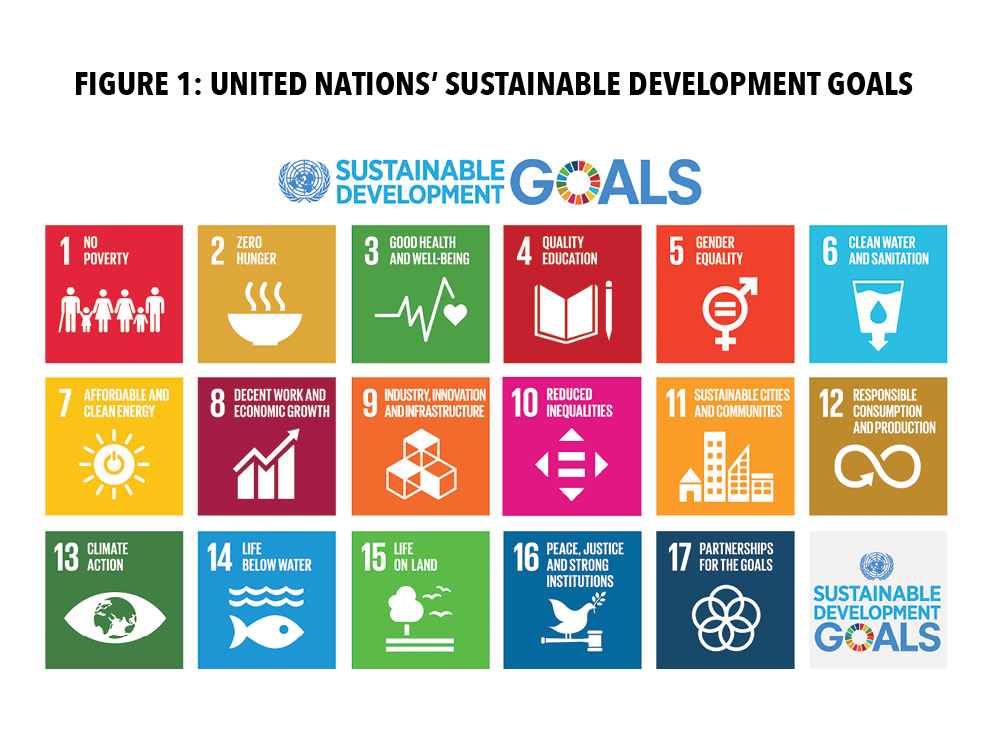

Rather than zealously advocating for companies to fix all the problems, we must carefully consider limitations on what corporations can and should do—and understand that some elements should be left to governments and NGOs. For example, in looking at the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), many of them aren’t the direct responsibility of corporations (see Figure 1). Sometimes, for example, it can be difficult to see the direct link between corporations’ actions and SDGs like Zero Hunger or Quality Education.

As educators, our first task is to level set students to encourage the right frame of mind. That involves identifying the urgent issues that businesses must address, while showing students how real progress is being made. To get students to become appropriately critical, we must help them understand the intersection of: “Awful, better, could be better,” (see Figure 2) a mindset inspired by a blog post regarding the state of global child mortality. The author lays out evidence that child mortality is simultaneously:

- Awful: A significant issue in much of the world.

- Better: Compared to all of human history, child mortality is now greatly reduced.

- Could be better: Millions of children could be saved if we could decrease every country’s mortality rates to match those of the European Union.

This is precisely the type of framing students should use to understand business and sustainability.

- Awful: Businesses still significantly contribute to sustainability issues, such as climate change; contaminating water, land, and air with chemicals and microplastics; and myriad other issues.

- Better: All large public companies now report regularly on sustainability and social impact issues. Hundreds of companies have signed on to science-based targets to reduce carbon emissions. Additionally, many companies have made significant strides to foster more inclusive workplaces. For instance, women now make up 33% of board members for S&P 500 companies, up from only 18% just a decade ago.

- Could be better: There’s always room for improvement. For example, greenhouse gas emissions in some sectors were nearly four times higher for the worst-performing companies than the best-performing companies, according to a research article published in Science in 2023. In all sectors, there was a substantial gap between the cleanest and dirtiest firms. While moving the dirtiest firms to the level of the cleanest wouldn’t be enough to solve climate change, it would make a substantial difference in our trajectory.

The first step in teaching business students about sustainability is to transform their hopelessness into guarded optimism. This happens by raising awareness that real progress is occurring while pointing out that there is still much left to be accomplished.

Acknowledge the Challenges of Integrating Sustainability and Business

Students (and business managers) might wonder: If sustainability were profitable, wouldn’t businesses already be doing it? This thinking is simplistic and reductive. There are plenty of businesses that have found profitable sustainability opportunities. The mindset that all sustainability efforts are costly is dangerous and short-sighted. For example, there is evidence that green buildings are financially advantageous for owners and occupants. In fact, companies that view sustainability issues as an opportunity to innovate can improve their products and/or lower their costs.

However, achieving profitable sustainability isn’t necessarily easy. Implementing any meaningful sustainability effort involves organizational change, and that can be difficult even at the best of times. There are widely varying estimates of what percentage of change efforts (whether sustainability related or not) succeed, but whatever number you want to use, it’s clear that change remains difficult for organizations. Changing to become more sustainable might be even more challenging, because it often involves a radical shift in processes and structures, as well as capabilities and mindsets. For example, over a decade ago Auden Schendler provided a compelling account of his efforts to enact changes at Aspen Ski Company. He explained how difficult it was to earn executive buy-in to his proposed changes, even when C-suite members were genuinely interested in improving organizational sustainability.

Getting profit-focused people to learn about sustainability can be considered an exercise in managing change. You need to help them apply all the same discipline to sustainability initiatives that they would to other transformations. You would never teach a student to undertake a technological transformation in their business without considering issues like creating urgency, setting and measuring progress toward goals, and considering contextual factors like the company’s culture and capabilities. Getting students to grapple with these issues (and more) and how they can trip up sustainability efforts is vital in establishing credibility.

Furthermore, we have found that it helps to frame sustainability initiatives in terms of tradeoffs. Students are well-accustomed to thinking about risk and reward in investments and technologies. Sustainability is no different. There are plenty of low-risk/low-impact initiatives that a firm can launch to spark their sustainability journey. Energy-savings initiatives, for example, often have extremely short payback periods, and many are painless to implement. These initiatives limit risk exposure because they’re relatively contained and not very disruptive. But eventually, most firms will need to consider far more risky actions, such as transforming products (think of electric vehicles and how disruptive they are to the automobile industry). Such endeavors bring the possibility of much larger rewards, but also induce far greater costs and risks.

Today’s students are incredibly receptive to this message. They want to work for companies that are moving in the right direction on sustainability issues, and they want to be part of the solutions. But they also want to know how challenging this can be to prepare and build the skills they need to overcome these obstacles.

Stress Cogent, Empirically Testable Arguments for Sustainability Increasing Profitability

As finance professionals and educators, we know that two levers can improve profitability: increased revenue and reduced costs. Thinking about revenue increases, many well-meaning students will say things like, “Customers will pay more for sustainable products.” Of course, some customers will pay more for some sustainability features—but how many, and how much more? In reality, most customers won’t buy “sustainable products” for altruism alone. To reach a large market, we need to consider both altruism and egoistic motivations, such as quality, health, emotion, money and status.

As a result, we need to challenge students to understand the market appetite for price increases. Raising prices can create other problems, especially in the current economy. Getting students to think about when consumers might value sustainability features, and to what degree they might do so turns the discussion from leaning on opinions into one of rigorous academic debate

Drawing on rigorous work has two key advantages:

- It lends credibility to the arguments you’re making. For example, some companies argue that showing a commitment to sustainability initiatives helps attract and retain top talent. But we must dig deeper by pairing those claims with evidence from meticulous research. For example, there is strong evidence that gig employees are more willing to accept jobs at socially/environmentally proactive organizations.

- It is careful to spell out its limitations. Discussing those limits can truly stretch students’ critical thinking. For the gig employee research, a natural question is: “Will this hold for long-term employees?” Students can engage with reasons why it might (long-term employees are likely to have greater identification with an employer and be personally affected by its stances) or might not (so many other factors matter for long-term employment that the social responsibility element could be muted).

Students need to know how to draw on reliable research studies to help their companies understand the potential implications of sustainability changes being considered.

Avoid The Traps of Cheerleaders and Know-It-Alls

Experience doesn’t just teach us what to do. It also offers us many opportunities to learn what to avoid when engaging business students in sustainability.

- Don’t focus entirely on darlings. Students love Patagonia, and most are aware of the company’s mission and sustainability efforts. They know Patagonia’s success as measured by brand awareness, ability to achieve high prices for products, and excellent customer experiences. But Patagonia’s experiences are the exception, so they are less instructive than the actions of other companies.

- Don’t be a cheerleader. It’s okay to challenge students’ arguments, but you also need to maintain a classroom culture of acceptance and diverse thinking. If students feel uncomfortable disagreeing with the professor or most classmates, you’ve failed. Students will enter a sustainability class with varying degrees of skepticism about the role a business can or should play in fixing the myriad issues society faces. If you’re too much of a cheerleader, you’ll alienate the students who have valid concerns and will have done little to sharpen the critical thinking of those who believe that business has a role in sustainability issues.

- Don’t be a know-it-all. Purporting to know everything is both disingenuous and dangerous. On this rapidly changing topic, instructors need to update their courses and knowledge constantly. Don’t be afraid to acknowledge what you don’t know. We’re experts in accounting and management—not chemistry, engineering, psychology, etc. We need to facilitate discussions that fit squarely in our knowledge base and admit when we (or our students) need to do more research. In a space that’s evolving rapidly, it’s critical for us to always seek clarity and adapt. The same goes for businesses. New issues pop up regularly and managers need to constantly engage with stakeholders to stay on top of challenges.

Being open to learning must sustain beyond the classroom. A graduate who implemented sustainability initiatives for multiple consumer packaged-goods companies recently told us that one of the biggest impediments she’d seen to getting sustainability improvements done was getting managers to learn from scientists. Learning starts with humility—knowing what you don’t know. If we want students to embrace that, we need to model it, too.

The Big Picture: Sustainability and Profits

No matter what the makeup of your class might be, your students need to understand how far businesses have come—and how far they still must go. They need to think about how challenging it can be to incorporate sustainability solutions in businesses. They must put aside bias and emotions and instead bring rigorous and relevant research into discussions. Instructors can’t fall into the trap of pretending to know everything. There’s always more to learn. Students want and need real instruction and the opportunity to think through these complex issues. After all, getting sustainability improvements enacted in their companies will be messier than a classroom discussion, and our job is to prepare them for those challenges.