Developing a clear distinction between liabilities and equity has long been the object of significant amounts of time, energy, and attention in the accounting profession. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) continues to issue Accounting Standards Updates (ASUs) that aim to clarify the distinction between liabilities and equity for hybrid financial instruments, and there are ongoing projects related to this topic on the FASB’s technical agenda.

Despite the ongoing attention to this issue, a clear distinction between liabilities and equity is nowhere in sight. Rather, it appears that guidance on this issue is only getting more complex.

THE PROBLEM: CREDITORS VS. OWNERS

The fundamental problem that impedes the development of a clear distinction between liabilities and equity is the adherence to the notion that liabilities should reflect the interests of those that lend money to a business (creditors) and that equity should reflect the interests of those that own the business (owners). This simple binary distinction is useful in the sense that creditors and owners are differently exposed to the economic performance of the business. Specifically, an owner’s prospects for future cash flows improve when the business performs well but worsen when the business performs poorly. In contrast, a creditor’s prospects for future cash flows are generally fixed by a contract (e.g., a bond or note) and, therefore, don’t fluctuate with the performance of the business as long as poor performance doesn’t threaten the ability of the business to fulfill the contract. Because the creditor is contractually entitled to cash flows and the owner isn’t, it’s reasonable to conclude that the creditor’s interest represents a liability to the business, while the owner’s interest doesn’t.

While this approach to distinguishing liabilities from equity is simple for bonds and common stock, it isn’t so simple for many other types of financial interests. Consider that there are countless ways in which a financial interest can be structured to adjust the degree to which it’s exposed to the economic performance of the business. For example, various classes of preferred stock differ in the amount to be paid as dividends or the timing with which the shares are to be settled (i.e., redeemed), thus limiting the preferred shareholder’s exposure to economic fluctuations relative to a common shareholder.

Conversely, convertible bonds provide the bondholder with an option to convert bonds to shares of common stock, thus increasing the bondholder’s exposure to economic fluctuations relative to holders of nonconvertible bonds. Examples like these illustrate the idea that exposure to the economic performance of a business isn’t binary, but rather, exists along a continuum. In other words, there can be different degrees of exposure to economic performance that don’t neatly conform to the binary creditor-owner categories.

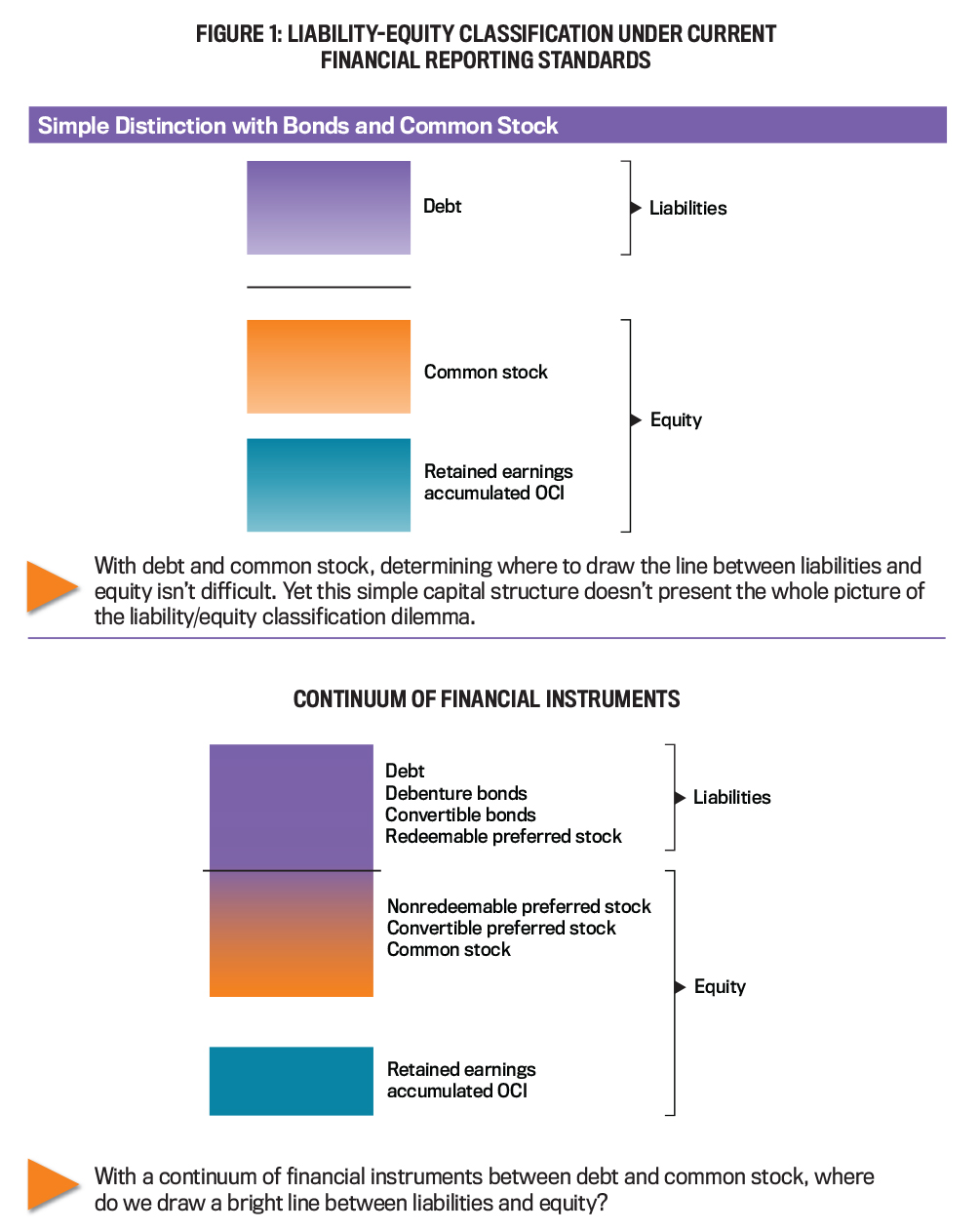

Figure 1 illustrates the challenge in distinguishing liabilities and equity. The classification of common stock and bonds is simple: Bonds are classified as liabilities, while common stock, along with retained earnings and accumulated other comprehensive income (OCI), is classified as equity. Yet the full continuum of financial instruments between bonds and common stock, which exposes the owner in varying degrees to the economic performance of the business, complicates the question of where to draw the line between liabilities and equity.

The existence of this continuum lies at the heart of the problem with basing the liability-equity distinction around creditors and owners. Accountants are left with the unenviable task of drawing a bright line somewhere along this continuum to differentiate creditors from owners. The point at which this bright line is drawn, however, is unavoidably subjective and arbitrary, which in turn fuels a perpetual debate over the distinction between liabilities and equity.

THE SOLUTION: THE EARNED CAPITAL APPROACH

We propose a solution to the liability-equity problem that untethers the distinction between liabilities and equity from the distinction between creditors and owners. Under this proposed solution, which we refer to as the “Earned Capital Approach,” the distinction between liabilities and equity is based on the distinction between a business’s two sources of capital: (1) the capital it acquires from issuing claims to investors and creditors (“external capital”) and (2) the capital it acquires from selling its goods and services (“earned capital”).

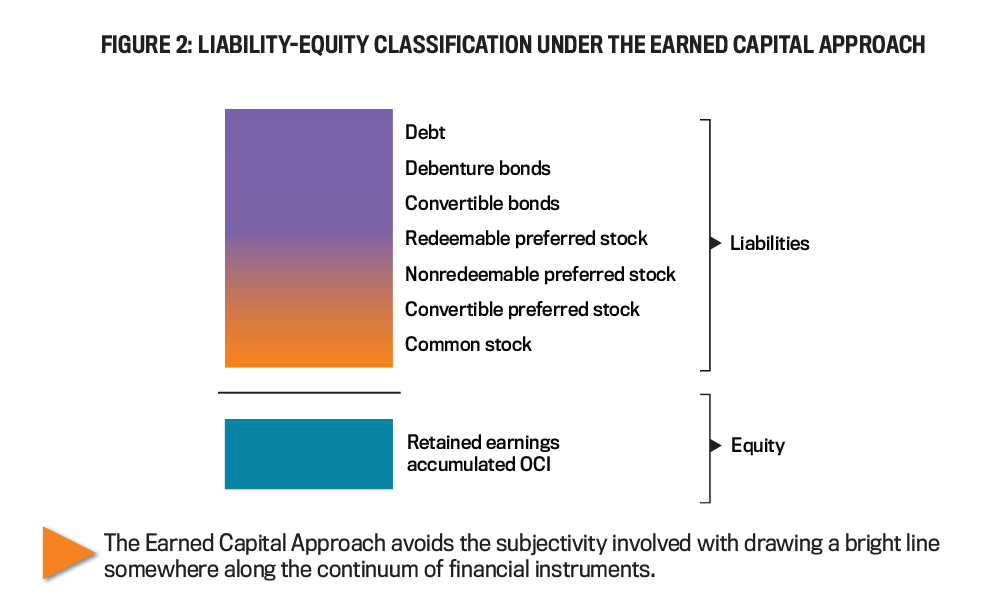

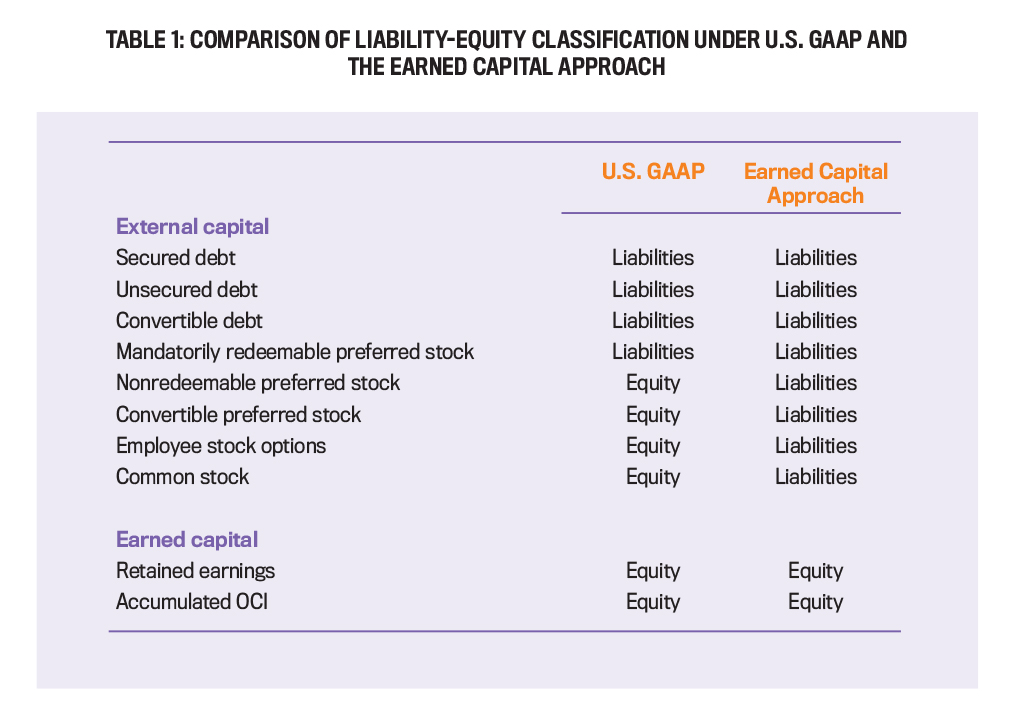

In terms of the balance sheet, external capital includes all liabilities and the contributed capital portion of stockholders’ equity, whereas earned capital includes retained earnings and accumulated OCI. We illustrate our proposed solution in Figure 2. Under the Earned Capital Approach, liabilities include all external capital, whereas equity includes only earned capital. Table 1 presents a comparison of some common liability-equity classifications under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP) with those under the Earned Capital Approach. Note that external capital classified as equity under U.S. GAAP (e.g., common stock) is classified as a liability under the Earned Capital Approach.

We presented this solution in a published academic article in the March 2021 issue of Accounting Horizons titled “An Alternative Approach to Distinguishing Liabilities from Equity.” This summary version is provided here for practitioners’ consideration. The Earned Capital Approach has both practical and theoretical advantages over the U.S. GAAP approach to distinguishing liabilities from equity, including the following:

1. It resolves the ambiguity in distinguishing liabilities from equity. Much of the debate around distinguishing liabilities from equity has revolved around classifying different types of external capital that possess characteristics of both creditor interests and owner interests (e.g., preferred stock, convertible debt, and employee stock options). These debates often get into the weeds of specific contractual terms.

These questions are irrelevant under the Earned Capital Approach because the specific contractual terms of external capital don’t affect the liability/equity classification. As illustrated in Table 1, all external capital is classified as a liability regardless of the specific contractual terms. This has the practical benefit of making the distinction between liabilities and equity easier to implement for financial statement preparers.

For financial claims that possess characteristics of both debt and stock, preparers wouldn’t be burdened with sifting through complex financial reporting requirements to determine whether such claims belong in the liabilities or equity categories. Rather, they simply classify these claims as liabilities. Additionally, there’s a clear and obvious distinction between the financial claims issued to investors and creditors and the goods and services provided to customers or purchased from suppliers. Therefore, the ambiguity in liability-equity classification is virtually eliminated under the Earned Capital Approach.

2. It provides for a conceptual definition of equity. Equity is calculated by subtracting liabilities from assets. Yet equity lacks a clear conceptual definition under current financial reporting standards because it represents both the accumulation of net amounts earned from selling goods and services and net amounts acquired from issuing claims to various classes of shareholders—two fundamentally distinct activities.

The Earned Capital Approach remedies this problem by excluding from equity amounts acquired from issuing claims to shareholders. Specifically, under our approach, equity is defined as the accumulation of net amounts earned from selling goods and services.

3. It improves financial statement articulation between the balance sheet and statement of comprehensive income. Under current financial reporting standards, it’s difficult to understand how comprehensive income relates to the change in stockholders’ equity. To understand the total change in stockholders’ equity, a financial statement user must consider comprehensive income, stock issuances, repurchases, and dividends.

Under the Earned Capital Approach, however, the change in stockholders’ equity equals comprehensive income. Simplifying this articulation between the balance sheet and statement of comprehensive income allows users to more clearly observe the relationship between a company’s comprehensive income and its financial position.

4. It aligns the format of the balance sheet with that of the income statement and statement of cash flows. The balance sheet under the Earned Capital Approach presents accumulations of capital earned from selling goods and services in a separate category (i.e., equity) from accumulations of capital received from the issuance of claims (i.e., liabilities). This is consistent with the formats of the income statement and statement of cash flows under current financial reporting standards.

Specifically, the income statement presents amounts earned from selling goods and services and excludes amounts received from issuing claims, and the statement of cash flows presents cash received from selling goods and services in a separate category (i.e., operating activities) from cash received from issuing claims (i.e., financing activities). In our view, this alignment of financial statement presentation allows users to more clearly understand the relationships between the financial statements.

CLAIMS OF COMMON SHAREHOLDERS

Perhaps the most controversial implication of the Earned Capital Approach is that the claims a business issues to its shareholders (i.e., shares of stock) are classified as liabilities rather than equity. Under current financial reporting standards, these shareholder claims are reported in the stockholders’ equity section of the balance sheet and are commonly referred to as “contributed capital” or “paid-in capital.” Under the Earned Capital Approach, paid-in capital is reported in the liabilities section, and the equity section consists only of earned capital (i.e., retained earnings and accumulated OCI).

The classification of shareholder claims as liabilities may elicit skepticism. Therefore, we discuss some possible objections to the prospect of classifying shareholder claims as liabilities.

1. Shareholder claims don’t meet the FASB definition for liabilities. The key concept on which the FASB definition for liabilities hinges is “present obligation.” It’s unlikely, however, that many will view an outstanding share of stock as a present obligation because the timing and amount to be repaid isn’t specified contractually. There are two paths to resolving this problem.

The first path is to expand the concept of “present obligation” to include obligations to shareholders. An outstanding share of stock can reasonably be characterized as a present obligation if we consider the arrangement between a company and a shareholder. The shareholder has supplied capital to a company in exchange for a share of stock. This share of stock grants the shareholder the right to receive an economic benefit in the future as compensation for providing use of capital. The existence of this right is recognized under current financial reporting standards in that the shareholder records the share of stock as an asset (i.e., a present right to an economic benefit) on its financial statements. If one accepts that the holder of a share of stock has a present right to an economic benefit, one should also accept that the issuer of the share of stock has a present obligation to transfer that economic benefit.

The second path is to replace the concept of “obligation” with that of “expectation.” If revising the concept of “present obligation” to include obligations to shareholders is a bridge too far, we alternatively propose replacing the concept of present obligation with that of “present expectation.” By present expectation, we mean that there’s a reasonable expectation between the holder of a claim and the business that issued the claim that the business will transfer an economic benefit to the holder in the future. How do we know if a present expectation exists? The simple answer is that the issuance itself is objective and observable evidence of a present expectation.

For example, consider a bond issuance. To the issuing company, the bond represents an expectation to transfer an economic benefit not simply because there’s an explicit legally enforceable requirement that it make such a transfer but, on a deeper level, because the bondholder wouldn’t have willingly paid for the bond without an expectation of an economic benefit in the future.

We can apply this same logic to the case of a share of common stock. That is, a share of common stock represents an expectation for the issuing company to transfer an economic benefit because the shareholder wouldn’t have paid for the share had there not been an expectation of receiving an economic benefit in the future. In other words, the issuances of the bond and share of common stock in these examples serve as the objective and observable evidence that they represent expectations to transfer economic benefits.

One important point of clarification with the concept of present expectation is that it doesn’t open the door to the recognition of any and all expected future transactions. For a present expectation to exist, there must be some past transaction or event with another entity (e.g., an issuance of stock). We aren’t suggesting, for example, that a business recognize a liability for the wages it expects to pay to employees in future years. Rather, the business only has a present expectation to pay wages if the employees have performed the work for which the wages are earned.

One could argue that shares of common stock don’t always represent expectations of future sacrifices of economic benefits because not all companies pay dividends and not all shares are routinely repurchased. Yet we contend that all shares of common stock, regardless of the issuing company’s dividend policy or share repurchase activity, derive their fundamental value from underlying expected future cash flows. That is, a share of stock has value only to the extent that investors expect future cash flows. These cash flows can take the form of cash dividends or stock repurchases for companies operating as a going concern or liquidating dividends for companies in financial distress.

If we accept the notion that a share of stock constitutes a present expectation only if the issuing company pays dividends or routinely repurchases shares, then from where does a share of stock issued by a nondividend-paying, nonshare-repurchasing company derive its value? One possible answer to this question is that a share of stock derives value from the fact that its shareholder can sell it to another shareholder for a gain (i.e., stock price appreciation). While this is true, it raises the question of why the new shareholder is willing to purchase the share from the prior shareholder in the first place. In essence, this question leads us back to the original question: Where does a share of stock derive its value if not from the expectation of future cash flows? If we continue to answer this question by asserting that the new shareholder can sell the share of stock to yet another shareholder, we become caught in an infinite regress that fails to explain the fundamental source of a share’s value.

An increase in stock price is simply an increase in the expected future cash flows underlying the share. A shareholder that realizes a gain on an increase in stock price has merely profited from an increase in the share’s underlying expected future cash flows. While the shareholder may not have collected any cash flows from the company in the form of dividends or share repurchases, it was possible to sell to another investor the expectation of such cash flows in the future. Consequently, as long as a share of stock remains outstanding and has a nonzero stock price, there’s a present expectation for the company to transfer economic benefits to the shareholder in the future.

2. Shareholder claims shouldn’t receive the same classification as debt claims. Some may argue that shareholder claims shouldn’t receive the same classification as debt claims because doing so would de-emphasize important distinctions between shareholder claims and debt claims. This, in turn, could hinder the ability of financial statement users to assess financial risk with traditional leverage ratios. Our proposed classification of shareholder claims as liabilities doesn’t imply that shareholder claims are the same as debt claims. Rather, we recognize the need to maintain a distinction between different types of claims on the balance sheet.

One way to emphasize distinctions between different types of claims is to implement a system of subclassifications within the liabilities classification based on key contractual terms. We currently separate liabilities based on timing of settlement (e.g., current vs. noncurrent).

This subclassification scheme could be expanded to highlight additional differences in contractual terms. Under a more expansive system of subclassifications, shareholder claims would be presented separately from bondholder claims, as well as other types of liabilities. Consequently, users would be able to assess financial risk with traditional leverage ratios under the Earned Capital Approach just as they are under current financial reporting standards.

3. Classifying shareholder claims as liabilities implies that cash distributions to shareholders are expenses. One consequence of treating shareholder claims as liabilities is that dividends and share repurchases (i.e., the portion of the repurchase above the original issue price) would be reported as expenses on the income statement. This treatment violates a fundamental convention that transactions with shareholders don’t result in revenues, expenses, gains, or losses.

As a counter to this convention, however, we argue that shareholder distributions represent an economic cost to the company. By recognizing these costs on the income statement, shareholder distributions are treated like distributions to employees (i.e., salaries and wages), suppliers (i.e., cost of goods sold), and creditors (i.e., interest). Additionally, net income represents a measure of the business’s income rather than a measure of shareholders’ income. The income statement could be presented with dividends in a different section, allowing users to distinguish between operating income vs. other activities, similar to the possible subcategories of liabilities described in the discussion of the second objection.

4. Earned capital is also a shareholder claim. Some may argue that it’s appropriate to classify paid-in capital and earned capital similarly as equity because shareholders have claims on earned capital just as they have claims on paid-in capital. In contrast to this perspective, we argue that no entity, aside from the business itself, has a claim on its earned capital.

Additionally, acquiring earned capital from selling goods and services, unlike acquiring external capital from issuing shares of stock, doesn’t concentrate or dilute a shareholder’s interest in the business. Although it’s true that shareholders are paid dividends out of the business’s earned capital, this doesn’t imply that earned capital is a claim of the shareholders. The observation that dividends are paid out of earned capital is similarly true for interest paid to bondholders, salaries and wages paid to employees, and the cost of goods and services paid to suppliers. Yet it’s nonsensical to argue that earned capital represents the claims of any single class of external entities (e.g., bondholders, employees, and suppliers). Earned capital is used by the business to satisfy any of these various claims.

The Earned Capital Approach addresses a problem that has long plagued the accounting profession: distinguishing liabilities from equity. Rather than taking the fruitless approach of distinguishing creditor interests from owner interests, the Earned Capital Approach relies on a distinction between earned capital and external capital. Because there’s a clear and obvious distinction between earned capital and external capital, the immediate practical benefit of the Earned Capital Approach is the elimination of complex financial reporting standards. This alleviates the burden on both standard setters that are perpetually debating and updating these standards and financial statement preparers who are tasked with interpreting them.

June 2023